Rights, Riparian

Water law today is primarily a product of statutes enacted by legislatures and regulations issued by implementing administrators, although reviewing courts remain important in the system. Modern law is being increasingly accommodated to ecosystem values—rather than solely to human demand—in establishing a "law of reason" for all water. This makes sense because water is part of a single hydrologic cycle. Precipitation in a humid zone contributes to streams, lakes, and wetlands , or seeps into the ground to reappear in wells and springs, ultimately to reach the ocean and again return (except for a very small amount) to precipitation. * Along the way, water provides a necessary resource for human use, as well as ecosystems dependent on water.

The humid zones of eastern North America had little water law before the 1820s. The rule that developed is called the riparian doctrine and is part of the common law of the property tradition. The riparian doctrine in the United States exists as a legal structure for the human use of stream water in the "humid states": specifically, the states east of the first tier of states west of the Mississippi River.

The original definition of "riparian" derives from its Latin origin, ripa , meaning "bank of a stream." But in law, the term "riparian" may refer to land different than what geographically extends away from the stream. Legal definitions may be as inclusive as all the land under the continuous title of the same landowner whose ownership begins beside the stream.

Evolution of the Riparian Model

Understanding the traditional form of the riparian water law model helps in the modern legal understanding of water rights and use. The content of

The courts called the traditional rule the "natural flow doctrine." Under this doctrine in its purest form, the courts asserted the riparian landowner (the owner of riverside land) was entitled to receive and return water to a stream as it came naturally to their land: that is, the landowner could use the stream without changes to its flow, volume, temperature, and quality. But as water demands increased in agriculture and industry, the courts modified the rule: some say courts adopted a new rule. In any case, the courts expanded the reasonable use idea so that maintaining the purely natural condition of the stream was no longer required.

It should be remembered that under common law, the riparian landowner's interests in the river's water was protected. Yet the common law did not provide much protection to streams as public resources. Other legal rules provided that flowing water belonged to the public and that states could not transfer certain public waters to private parties in violation of public trust . Although these rules put few limits on riparian rights concerning streams, some other legal rules restricted what a riparian landowner could do with a stream. The riparian controlled access to the stream, but could not admit an unlimited number of users nor let an unlimited amount of water be transferred elsewhere. Doing either would be considered "unreasonable" at the least.

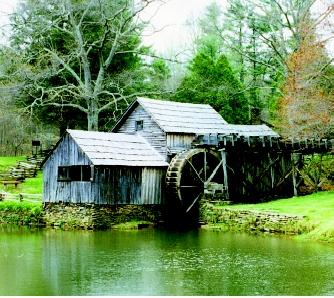

Mill Privilege.

Although the riparian landowner had no absolute control over access, sale, and use, one very significant exception existed, thereby conferring absolute power on a few riparian landowners. This was the mill privilege. A riparian landowner could receive a right to dam a stream to turn a mill wheel

Today's Framework

Legal doctrines change over the course of time. In modern water law, legislatures are playing a more active role, in humid as well as arid states, because water supply cannot keep pace with human demand. Permits are increasingly required. Riparian landowners still have their powers and rights, but they are not what they were even a few decades ago. Reasonable use today in law emphasizes the full and beneficial employment of the stream for economic and other advantages that will insure the stream's living character.

SEE ALSO Law, Water ; Prior Appropriation ; Rights, Public Water.

Earl Finbar Murphy

Bibliography

Getches, David H. Water Law in a Nutshell, 3rd ed. St. Paul, MN: West InformationPublishing Group, 1997.

Tarlock, A. Daniel. Law of Water Rights and Resources (Environmental Law Series). NewYork: Clark Boardman Callaghan, 1988 (with annual supplements 1989–2002).

* See "Hydrologic Cycle" for an illustration of the water cycle.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: