Pollution of the Ocean by Plastic and Trash

Garbage has been discarded into the oceans for as long as humans have sailed the seven seas or lived on seashores or near waterways flowing into the sea. Since the 1940s, plastic use has increased dramatically, resulting in a huge quantity of nearly indestructible, lightweight material floating in the oceans and eventually deposited on beaches worldwide.

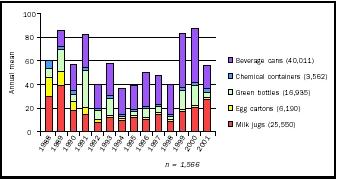

As the graph shows, trash items encompass a variety of materials. Sources of marine debris include:

- Items that are brought to the beach and left there by beachgoers;

- Garbage deliberately or accidentally discarded by ships at sea or from offshore oil platforms; and

- Material carried to sea by rivers and estuaries , especially from large coastal cities.

City storm sewers are a significant source of solid waste entering the sea from land sources.

Effects on Wildlife

Aside from its unsightly appearance and potential impact to human health, marine debris has harmful effects on wildlife. Fish, birds, marine mammals, reptiles, and other animals can become entangled in discarded or lost nets that continue to do what they were designed to do—catch living animals—but now they catch them indiscriminately, a process called "ghost fishing." Items unintended for fishing become traps.

Woven plastic onion sacks floating in the sea have entrapped endangered hawksbill sea turtles. Plastic bags become invisible to birds diving for

Efforts to Reduce Debris

Unsightly littered beaches gained public attention in the early 1980s and efforts were made to find out how much garbage there was, where it came from, and what its effect was on ocean wildlife. Medical waste and other floatable debris washing ashore at public beaches of the eastern United States, primarily in New York and New Jersey, was a particularly disturbing and highly publicized aspect of ocean pollution by municipal solid waste. The incidents in New York and New Jersey spurred the 1988 passage of the federal Medical Waste Tracking Act (which has since transferred to individual states) as well as subsequent federal and state laws designed to better regulate the handling, treatment, transportation, and disposal of medical waste. Since the early 1990s, medical waste in U.S. coastal waters has faded from public view, and is not considered a public or environmental health threat associated with ocean dumping, primarily because it comprises only a small percent of municipal solid waste items found in the ocean. However,

Scientists and environmental groups since the 1980s have more closely addressed the problem of marine debris and its effect on public health and wildlife. The general public has helped in organized beach cleanups using data sheets to record the types and numbers of items found. Cleanups were at first limited to beaches bordering the United States ocean coastlines, but soon international efforts were organized, and cleanups were also done along riverbanks, lakeshores, marinas , and even by divers to recover submerged items along jetties and fishing piers.

MARPOL.

Due in part to the public attention paid to marine debris, an international agreement (MARPOL, or The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution by Garbage from Ships; Annex V) was reached by many of the world's governments to prohibit or limit the quantity of garbage that can be discharged at sea or in waterways that lead to the sea. (The United States ratified Annex V in 1987.) In some areas like the Gulf of Mexico, there is a total ban on discharging plastics into the sea. All vessels must carry signs informing crews of the laws and must provide containers for different types of materials that will be offloaded at the next port of call rather than dumped into the sea.

Persistent Problem.

After the United States ratified MARPOL Annex V in 1987, the quantity of marine debris decreased, but has increased again in recent years. Solutions include:

- Improving the general public's awareness, concern, and attitude towards littering;

- Reducing the use of plastic and other materials for disposable packaging; and

- Enforcing existing laws, especially at sea, to punish habitual litterers.

As the twenty-first century opened, marine debris continued to wash ashore on beaches around the world, including the United States. There has been some reduction in the quantity of trash on America's ocean beaches, partly because of adherence to the law, partly because of self-imposed company rules, and partly owing to increased public awareness. Much of the credit for this must be given to the beach cleanups that have given the public a first-hand look at the problem. Even so, marine mammals, reptiles, birds, and other ocean life continue to sustain injuries from ingesting or becoming entangled in plastic debris and fishing gear.

SEE ALSO Beaches ; Coastal Waters Management ; Human Health and the Ocean ; Ocean Health, Assessing ; Pollution of Streams by Garbage and Trash ; Pollution of the Ocean by Sewage, Nutrients, AND Chemicals ; Wastewater Treatment and Management .

Anthony F. Amos

Bibliography

Amos, Anthony F. Solid Waste Pollution on Texas Beaches: A Post-MARPOL Annex V Study: OCS Study MMS 93-0013 New Orleans, LA: U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, vol. 1, 1993.

Center for Marine Conservation. A Citizen's Guide to Plastics in the Ocean: More than a Litter Problem. Washington, D.C.: Center for Marine Conservation, 1994

Coe, James M., and Donald B. Rogers, eds. Marine Debris: Sources, Impacts, and Solutions. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996.

Committee on Shipborne Wastes, Marine Board Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems, National Research Council. Clean Ships, Clean Ports, Clean Oceans: Controlling Garbage and Plastic Wastes at Sea. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1995.

Internet Resources

Assessing and Monitoring Floatable Debris. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Oceans and Coastal Protection Division. <http://www.epa.gov/owow/oceans/debris/floatingdebris/toc.html> .

Marine Debris. The Ocean Conservancy. <http://www.oceanconservancy.org/dynamic/issues/threats/debris/debris.htm> .

Marine Debris Abatement: Trash in Our Oceans—You Can Be Part of the Solution. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Ocean and Coastal Protection Division. <http://www.epa.gov/owow/oceans/debris/index.html> .