Marine Mammals

What comes to mind when the subject of marine mammals is introduced? Most people probably only think of a few species of dolphins, whales, or

Marine mammals commonly are defined as mammals that require the ocean for most or all of their needs. Yet some scientists disagree on where to draw the line between terrestrial and marine mammals. Some regard a few species of bats and even the Arctic fox as marine mammals because they depend on food from the sea. Regardless of these more inclusive definitions, all true marine mammals have adapted to life in the water in wonderful ways.

Cetaceans

Cetaceans—whales, dolphins, and porpoises—spend their entire lives in water. Cetaceans are divided into two types: mysticetes and odontocetes.

Mysticetes.

Mysticetes, such as humpback, right, minke, and gray whales, have baleen instead of teeth that are used for filtering small fish and invertebrates from sea water. Blue whales, the largest of all animals on Earth, at up to 27 meters (90 feet) long, are included in this group. Most baleen whales make yearly migrations, feeding during the summer in colder water and traveling up to thousands of miles in warmer and shallower areas to mate and give birth 1 year after mating. Baleen whales also have a thick layer of blubber, which is used both for insulation in cold water and energy storage during migration and winter fasting.

Odontocetes.

The rest of the whales, as well as all dolphins and porpoises, are grouped together as odontocetes because they have teeth. Sperm whales, the largest odontocetes at up to 18 meters (60 feet) long, dive to as deep as 1.6 kilometers (1 mile), where they feed on deep-water fishes and squid. Most females of both sperm and pilot whales stay with their mothers their entire lives; but the males more often leave and form all-male groups. In sperm whales, they even live alone as "bachelors," only meeting up with other whales for breeding.

Although called a whale because of its size, the killer whale ( Orcinus orca ) is actually the largest member of the dolphin (Dephinidae) family. Killer whales, also often called orcas, have been studied most extensively in the Puget Sound off Washington state and British Columbia, where they are divided into two types: residents and transients.

Resident orcas eat fish and spend their lives in specific regions. Male and female offspring stay with their mothers their entire lives. Transient orcas eat primarily marine mammals, but even birds, turtles, or sharks are eaten on occasion. Transient orcas move between areas much more frequently; consequently, their family units are not as stable as the residents' units.

The smaller dolphins feed on a wide variety of organisms. Some, such as the pan-tropical spotted dolphin or the common dolphin, feed in the deep waters of the open ocean and are not seen by humans as often as the many species that come close to shore. Spinner dolphins have different forms: some live only in the deep ocean like those mentioned above, whereas others feed in deep water at night but rest in shallow bays during the daytime. Several dolphins, called river dolphins, live only in fresh water. Dusky dolphins of the southern hemisphere cooperate to herd schooling fish, to feed on them more successfully.

Bottlenose dolphins are very common in the wild and can be found close to shore almost anywhere except in Arctic and Antarctic waters. These dolphins feed on a wide variety of prey, mostly fishes, and many have adapted to living in areas close to humans. Flipper was a trained bottlenose dolphin that starred in a movie and a television show in the 1960s.

Porpoises are similar to dolphins, but tend to occur more often in colder waters. They also have different teeth, dorsal fin shape, and skull structure from those of true dolphins. The vaquita, or Gulf of California harbor porpoise, is endangered due to many individuals being killed in gill nets .

Sirenians

Manatees and dugongs are included in the order Sirenia. They are the only herbivores among marine mammals, feeding on sea grasses in tropical waters. They are slow-moving coastal animals, which is unfortunate for many manatees that often are struck by boats, being killed or severely injured. Because of their slow movements and inshore habitats, manatees often are kept successfully in large commercial aquaria.

Carnivores

The order Carnivora, of which cats and dogs are members, includes the pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses); sea and marine otters; and polar bears. All pinnipeds spend part of their time on land or ice but feed in the sea. Most mate on land or ice, and all need to be out of the water to give birth. The newborn pups are nursed anywhere from 3 days to 3 years, depending on species, and are mostly independent afterwards.

True seals, such as harbor seals, harp seals, or elephant seals, have thick blubber layers for insulation and have a strange way of getting around on land. They have to wiggle forward like an inchworm because their front flippers do not reach the ground. Despite their clumsiness on land, they are excellent swimmers. True seals have shorter infant care than the other pinnipeds.

Fur seals and sea lions have thinner blubber layers, and rely more on hair for insulation. They can walk on all four flippers, but generally do not dive as deep as the true seals. California sea lions are commonly trained to clap and play with balls in aquaria. Walrus, known for their long ivory tusks, occur only in the Arctic Ocean. They are also common entertainers in aquaria.

Sea otters and marine otters, both of the Pacific coast of the Americas, have the thickest fur of all marine mammals, and spend much of their time keeping it clean. Sea otters use their paws to gather shellfish to eat, and may even use rocks to crack open the shells. Marine otters cannot use their paws the way that sea otters do, and instead just grab prey with their mouths.

Although they do not spend as much time in the water as other marine mammals, polar bears are well adapted to life in the water. They swim with large paddle-shaped fore and hind feet, and feed on fishes in the water and seals on land or ice. Occasionally, they will even eat white whales and have been known to attack humans when threatened or approached too closely.

The Human Connection to Marine Mammals

Humans have had a long history of interaction with marine mammals, primarily with humans as hunters and marine mammals as prey. By the middle of the twentieth century, large-scale, unregulated whaling led to severe depletion of some populations. Within the last half century, recognition of this fact, combined with insights into the intelligence of marine mammals, has led to the emergence of protection and appreciation as the primary interactions between humans and marine mammals.

Aboriginal hunters of many coastal groups have long exploited whales, seals, sea lions, and other marine mammals for subsistence (survival) and, in the case of seals, fur. The effect of Native hunters on population levels was almost always small, unlike for some terrestrial mammals, because hunting large mammals on the open ocean is hard and dangerous, and an enormous amount of meat can be harvested from a single kill. Shore-dwelling seals are more susceptible to local extirpation, but even that was rare in the absence of commercial (rather than subsistence) hunting. Unregulated commercial hunting, however, can and has led to widespread decline in marine mammal populations. For example, fur seals were driven close to extinction in the 1800s by overhunting.

In colonial times, oil rendered from whale fat (blubber) was the main product that drove commercial whaling. Before the development of petroleumbased fuels, whale oil was widely used in lamps. Commercial whaling in the American colonies and elsewhere depleted coastal whale populations early on. Larger whaling ships and longer voyages further out to sea were the pattern in the 1800s, until exploitation of fossil fuels largely ended commercial whaling for oil.

Whaling for meat continued to be a commercially profitable enterprise, however, and the development of sea-based "factory ships" for processing whales led to continued decline in the numbers of whales. Recognizing the serious depletion of whale populations, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was founded by international agreement in 1946 to regulate the whaling industry. In 1983, the IWC decreed a moratorium on all commercial whaling, pending fuller understanding of the population dynamics and degree of endangerment of each commercial species.

Even with this moratorium, several aboriginal groups were allowed to maintain their traditional whale hunts. These include hunting of bowheads and greys by Northwest Coast and Eastern Russian Native groups; minke and fin whales by Greenlanders; and humpbacks by Caribbean Natives. Two countries—Japan and Norway—have attracted attention for continued whaling in the face of the moratorium, although each offers reasons why its whale catch falls within the few types of exceptions allowed by the IWC. * One such exception is for scientific research, and in part the controversy surrounds whether the research permits given out by these countries are simply used to skirt the regulations banning commercial harvesting. Despite these controversies, the ban on whaling has been an enormous success, and the populations of all types of whales have grown since the moratorium was instituted.

Other marine mammals have also been the subject of concern, most notably dolphins. While not a target of significant commercial harvesting themselves, they do get caught in large trawling nets designed to catch tuna. Like all mammals, dolphins must breathe air, and once caught in the nets, they drown. "Dolphin-friendly" tuna, which is not harvested via this fishing practice, is now marketed; international environmental monitoring groups work to ensure that companies that advertise dolphin-friendly tuna actually are using safe practices.

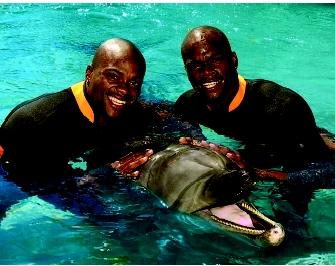

At the same time marine mammals were being increasingly protected from hunting, scientists increasingly came to appreciate the intelligence of marine mammals. It is no coincidence that the performing animals at Sea World and elsewhere are marine mammals: learning the tricks they display requires significant intelligence, which is not found in fish. While captivity continues to be the major environment in which humans interact with marine mammals, whale watching has become a significant tourist industry for some coastal towns, and it is even possible to "swim with the dolphins" in some warm-water bays. (In the United States, however, swimming with marine mammals is not legal.)

It is difficult to accurately compare the intelligence of different species, because the way humans measure intelligence often relies on skills possessed especially by themselves, such as language-based thinking and manipulation of objects with the hands. Despite these inherent limitations, it is clear that whales and dolphins are especially intelligent creatures, capable of solving puzzles and jumping through hoops for food rewards, and also having complex social systems and a type of "language." Researchers are attempting to understand these languages in hopes of learning more about these creatures and the societies they form.

SEE ALSO Arts, Water in the ; Ecology, Marine ; Food from the Sea ; Life in Water ; Pollution of the Ocean by Sewage, Nutrients, AND Chemicals .

Amy G. Beier (taxonomic orders)

Richard Robinson (human connection)

Bibliography

Berta, Annalisa, and James L. Sumich. Marine Mammals: Evolutionary Biology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999.

Cahill, Tim. Dolphins. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2000.

Reynolds III, John E., and Daniel K. Odell. Manatees and Dugongs. New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1991.

Reynolds III, John E., Randall S. Wells, and Samantha D. Eide. The Bottlenose Dolphin: Biology and Conservation. Gainesville, FL: The University Press of Florida, 2000.

Riedman, M. The Pinnipeds: Seals, Sea Lions, and Walruses. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990.

Sterling, Ian. Polar Bears. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1988.

Internet Resources

International Whaling Commission. <http://www.iwcoffice.org> .

FREE KEIKO

Keiko, the killer whale featured in the 1993 Hollywood movie Free Willy, was captured in the Atlantic Ocean near Iceland in 1979. In 1996, largely in response to increased public awareness about his captive living conditions, Keiko was moved to a custom-built facility at the Oregon Coast Aquarium, then to an open-ocean pen in an Icelandic bay in 1998.

With the help of his caretakers, Keiko underwent reintegration into Iceland's wild orca population through monitored interactions and ocean "walks." Keiko was allowed to wander free in January 2003, once other orcas had migrated to the same waters. Caretakers continue to support his reintegration, monitoring his health and progress.

* See "Sustainable Development" for a photograph related to Japan's whale harvesting.