Great Lakes

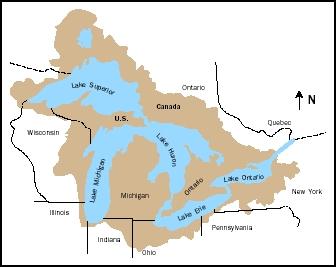

Located in north-central North America, the Great Lakes are five large fresh-water lakes interconnected by natural and artificial waterways: Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario. Carved by ancient glaciers, these lakes contain approximately 20 percent of the world's surface fresh-water supply and 95 percent of the surface fresh water in the United States. The Great Lakes waterbody is so large that its natural features can be seen from the Moon.

Great Lakes Watershed

Native Americans were the original inhabitants of the Great Lakes basin. Historically, the Great Lakes played a significant role in Native American societies and approximately 120 bands of native peoples have occupied this region over the course of history. Notable tribes inhabiting the Great Lakes region include the Chippewa, Fox, Huron, Iroquois, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Sioux. These Native peoples played an instrumental role when European explorers came to the region in the early 1600s, particularly in the development of the fur trade. Each of the names of the Great Lakes comes from either a Native tribe name or the Native words for the lakes.

Straddling the U.S.–Canada boundary, today's Great Lakes watershed is home to approximately 40 million Americans and Canadians. This population represents about 10 percent of the U.S. population and 25 percent of the Canadian population. In the United States, four of the twelve largest cities are located on the shores of the Great Lakes. The lakes constitute the largest inland water transportation system in the world, and have played an important role in the economic development of both the United States and Canada.

The Lakes.

The Great Lakes encompass 16,000 kilometers (10,000 miles) of inland coastal waters, and collectively have been referred to as "the inland seas" and "the fourth coast of the United States". Lake Michigan is located entirely within the United States, while the other four lakes form a partial border between the United States and Canada. The lakes are bordered by the Canadian province of Ontario and by the eight U.S. states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. The westernmost point of the Great Lakes is near Duluth, Minnesota, and the easternmost point is just north of Syracuse, New York (and connects with the St. Lawrence Seaway).

Covering a total surface area of about 244,000 square kilometers (94,000 square miles) the Great Lakes contain a volume of approximately 23,000 cubic kilometers (5,500 cubic miles) of water. This tremendous volume is hard to conceptualize, but if it were spread over the contiguous 48 states, its waters would average about 2.9 meters (9.5 feet) deep. Together the lakes drain about 750,000 square kilometers (about 290,000 square miles), with the primary outlet being the St. Lawrence River.

The shores of the Great Lakes vary considerably from region to region. On the eastern side of Lake Michigan, sandy beaches are prevalent, whereas the shores of Lakes Superior and Huron are primarily rocky, and often framed by cliffs comprised of sandstone and shale. Wetlands are found along Lake Ontario's shore, including Canada's well-known Point Pelee National Park. These shoreline systems serve to protect their inland areas by absorbing the force of wind and wave energy from the lakes.

Transportation

The Great Lakes and surrounding area is a natural resource of great importance in North America. The region also serves as the focal point of the industrial and agricultural base of the Midwest's heartland by providing a strong marine transportation system. Rivers, straits, canals, locks, and channels interconnect the Great Lakes, and together form one of the busiest shipping arteries in the world. *

With the 1959 completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway, the commercial potential of the lakes increased because they could now accommodate medium-sized oceangoing vessels. In fact, the St. Lawrence Seaway brought several Great Lakes ports closer to European markets than existing East Coast or Gulf ports, saving shippers both time and money. For example, the shipping distance from the port city of Baltimore, Maryland, to Liverpool, England, is 6,334 kilometers (3,936 miles). With the addition of the St. Lawrence Seaway, ships could reach Detroit, Michigan by covering only 5,911 kilometers (3,673 miles).

The Great Lakes today are home to the U.S. and Canadian flag fleets and to dozens of international vessels from ports around the world. The movement of shipping cargo is estimated to provide approximately 60,000 jobs throughout the Great Lakes region. The ability to efficiently ship materials such as iron ore, coal, and limestone enabled the rise of the steel and automobile industries in the Great Lakes region.

Recreation

Recreation in the Great Lakes area became important beginning in the nineteenth century. A thriving pleasure-boat industry based on newly constructed canals on the lakes brought vacationers into the region, as did the already established railroads and highways. The lower lakes wilderness region attracted people who were seeking health benefits and even miracle cures from mineral waters.

In the twentieth century, the U.S. and Canadian governments acquired border lands to develop a system of parks, wilderness areas, and conservation areas in order to protect valuable resources and to serve the recreational needs of the population. Unfortunately, by the time the need for publicly

Niagara Falls was one of the first Great Lakes tourist attractions, and it remains a popular destination. Niagara Falls were formed approximately 10,000 years ago when retreating glaciers exposed the Niagara escarpment, allowing the waters of Lake Erie to flow north to Lake Ontario. Until the early 1950s, the falls eroded at an average rate of 1 meter (3 feet) per year, but human modifications to the river's flow have since reduced the rate of erosion. Today, Goat Island splits the rapids into the American Falls (51 meters or 167 feet high and 323 meters or 1,060 feet wide) and the Horseshoe, or Canadian, Falls (48 meters and 158 feet high and 792 meters or 2,600 feet wide).

Great Lakes Fisheries

The Great Lakes support diverse fresh-water fisheries. Fish were a primary source of food to Native tribes of the Great Lakes region, and settlements often were established at places where the fisheries were good. Sturgeon, lake trout, and whitefish were popular catches of their time. Birchbark canoes and nets made from willow bark were commonly used to harvest fish. Tribal fishermen also practiced ice fishing, spearing through the ice and fishing with hand-carved decoys. Fish also were an important source of food to the early European settlers.

Commercial fishing began around 1820, and annual catches grew approximately 20 percent per year as improved fishing technologies were applied. During the 1880s, some species in Lake Erie began to decline. Commercial fishing harvests from the Great Lakes peaked between 1889 and 1899 at around 67,000 metric tons (147 million pounds).

By the late 1950s, the golden days of the Great Lakes commercial fishery were over. Since that time, average annual catches have been approximately 50,000 metric tons (110 million pounds). The fishery is increasingly dominated by smaller and relatively lower valued species. Moreover, the fishery is a mix of native and introduced species, with a number of species being restocked regularly. While each of the Great Lakes has its own mainstay species, common catches currently include lake trout, salmon, walleye, perch, whitefish, smallmouth bass, steelhead, and brown trout. *

In the 100 years since its peak harvests, the Great Lakes fishery has been severely threatened, mainly due to the effects of overfishing, shoreline and stream habitat destruction, and pollution. The accidental and deliberate introductions of nonnative invasive species, such as the sea lamprey and zebra mussel, have also played a role in the decline of this fishery. Today, only isolated pockets of the once large commercial fishery remain, and even these are uncertain, due largely to contaminants . Efforts undertaken to stabilize the commercial fishery have maintained its commercial and sport value at more than $4 billion annually as of 2002.

Environmental Degradation

The degradation of the Great Lakes can be traced back to the westward expansion of the North American population. The fishery decline in late 1800s was one of the region's earliest environmental problems. Agricultural and forestry practices resulted in siltation, increased water temperature, and loss of habitat for native fish species. The discharge of pollutants into the lakes accompanied the region's population growth. The vastness of the Great Lakes encouraged the mistaken belief that their great volumes of water could indefinitely dilute pollutants to harmless levels.

Yet impacts to the environment and human health were inevitable. The direct discharge of domestic wastes from cities along the lakeshores led to typhoid and cholera epidemics in the early 1900s. Moreover, fish would become so contaminated by municipal and industrial pollutants that their flesh was no longer safe to eat.

In 1909, the United States and Canada cooperatively negotiated the Boundary Waters Treaty. This treaty established the International Joint Commission (IJC) which is a permanent binational body addressing, among other important boundary issues, water quality concerns and the regulation of water levels and flows between the two countries. The Great Lakes Water Quality Board and the Great Lakes Science Advisory Board are bodies of the IJC. Six commissioners are the final arbitrators of the IJC: the United States and Canada appoint three each.

Several key water agreements have been produced by the International Joint Commission process, most notably the 1972 and 1978 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreements. Since the 1972 agreement, forty-three Areas of Concern (AOC) have been identified, twenty-six located within the United States, twelve located within Canada, and five that are shared by both countries.

Primarily due to the declining condition of Lake Erie, the 1978 Agreement went beyond setting narrow water-quality goals and addressed toxic contamination from an ecosystem perspective. This 1978 agreement has become a driver of the ecosystem approach to water management throughout the Great Lakes basin, and further amendments were passed in 1987. The 1987 U.S. Clean Water Act (Section 118) also addressed the Great Lakes situation and included provisions for monitoring of their water quality.

The Story of Lake Erie.

Reports since the 1950s of the "death" of Lake Erie serve as a reminder of the human impact on natural ecosystems. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Cuyahoga River, which empties into Lake Erie, caught fire due to oily pollutants on its surface. * Pollution problems from organic and inorganic wastes and nutrients were compounded by the effects of deforestation, sedimentation, and wetland drainage. Floating raw sewage, algal blooms, and the buildup of toxic metals in its sediments caused beach closings, oxygen depletion, contaminated fish advisories, and reports of the lake's death. Many feared the other lakes would follow a similar demise.

Concerted management efforts were undertaken in the 1970s to restore Lake Erie and the other lakes back to health. Yet after more than two decades of mostly good news about the lake's improving health, Lake Erie again is showing signs of an environmental crisis. Scientists attribute diverse and complex causes to the latest ecosystem disruption: large-scale fish and bird die-offs; a large "dead zone" off the Ohio shoreline; and the threat of invasion by more nonnative species, particularly the Asian carp and quagga mussel.

Renewed Concerns Over Water Levels

Measurements of water levels in the great Lakes constitute one of the longest continuous hydrometeorological datasets in North America. Reference gage records start in 1860, with sporadic records going back to the early 1800s.

Water levels on the Great Lakes change seasonally each year and can vary dramatically over longer periods. Seasonally, changes are to be expected, and the range of seasonal water-level fluctuation averages about 0.3 to 0.45 meters (12 to 18 inches) from winter lows to summer highs. Long-term fluctuations are harder to predict, and occur over periods of consecutive years. Over the last century, the range from extreme high to extreme low water levels has been nearly 1.2 meters (4 feet) for Lake Superior, and between 1.8 and 2.1 meters (6 to 7 feet) for the other Great Lakes.

As of 2002, the Great Lakes apparently were starting to recover from water-level lows not recorded since the mid-1960s. The declines probably were due predominantly to evaporation during the warmer-than-usual temperatures experienced during the late 1990s, a series of mild winters, and the below-average snowpack melts in the Lake Superior basin. Lower water levels have a variety of effects, including affecting shipping, recreation, property values, and habitat diversity. Concerns relating to potential impacts of global climate change on the Great Lakes are being researched.

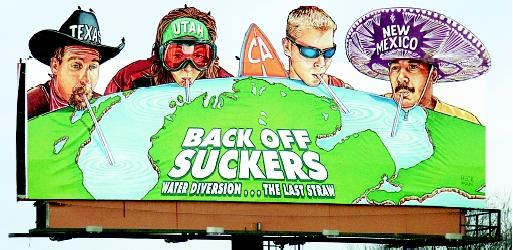

Diversion of Great Lakes Waters

Proposals to divert water from the Great Lakes hydrologic system have proven very controversial. As these lakes are a shared international resource, many governments and organizations are concerned with managing and protecting the integrity of the Great Lakes waters and ecosystem. For these groups, the bulk export of Great Lakes basin water is an increasing concern in a water-scarce world.

Existing diversions comprising sizable quantities of water involve Ontario, Canada; Chicago, Illinois; and the intrabasin transfers of the Welland Canal. These diversions have been operational since the early 1900s. Much smaller diversions involve New York, Wisconsin, Ohio (via the City of Akron), and Michigan (via the City of Detroit).

Since 1995, new diversion and export schemes have included:

- a permit granted to Perrier to bottle water from an aquifer in Michigan;

- a plan to divert millions of liters of groundwater per day from Lake Michigan's watershed for use in mining-related activities that would discharge much of the diverted water into the Mississippi River Basin;

- a permit issued by the Canadian province of Ontario for the bulk transfer of water from Lake Superior for sale in Asian markets as bottled water (but this permit was later revoked); and

- a 2002 proposal by the City of Detroit to bottle and sell water from the Detroit River.

Water diversions and exports have come under intense scrutiny, especially as the lake levels were falling and reached near-record lows. As levels rise, many see opportunities to use the waters of the Great Lakes for commercial uses and to make profits. A debate also has intensified over whether groundwater is part of "Great Lakes waters" as defined by the Water Resources Development Act of 1986.

Two policies have been enacted to attempt to govern potential diversions from the Great Lakes basin: the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 and the Great Lakes Charter of 1985. The Boundary Waters Treaty expresses a commitment by both countries to refrain from harming the waters of the other country (e.g., due to bulk exports). The Great Lakes Charter specifically urges U.S. governors and Canadian premiers in the region to seek each other's approval prior to granting diversion requests for large-volume bulk exports above a threshold level; however, this is a nonbinding treaty.

Additionally, U.S. diversions from the Great Lakes may also be subject to the Water Resources Development Act of 1986 (amended in 2000). This act requires the approval by all eight U.S. Great Lakes governors on any proposed exports out of the basin. Within the region, many are concerned that this policy is not strong enough to protect the lakes from diversions and several pieces of legislation have been introduced into Congress to help prevent future diversions and even to create a moratorium on these bulk exports.

While efforts to protect Great Lakes waters surely will continue, international free trade agreements may clear the path for additional diversions, bulk removals, or the selling of bottled water. On the other hand, ongoing concerns over impacts on lake levels and potential consequences from climate change may spur new laws and treaties to prevent future diversions and exports from the basin.

Future of the Great Lakes

Managing the Great Lakes system and implementing an ecosystem approach are made difficult by the myriad of agencies and programs with responsibility in this area. Two countries, eight states, two provinces, and numerous tribal councils and local jurisdictions share an interest in managing the waters of the Great Lakes. Many local citizens groups have also formed to address water issues.

A 2002 report by the International Joint Commission concluded that progress to restore and maintain the chemical and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes basin ecosystem is making some progress, but proceeding at a slow pace. It also stated that cleaning up contaminated sediments and stopping the invasion of alien species are two top priorities for restoring the chemical and biological integrity of this ecosystem. The Great Lakes basin has and will continue to serve as a vast laboratory where scientists can learn more about both ecosystem and water management.

SEE ALSO Algal Blooms in Fresh Water ; Canals ; Clean Water Act ; Economic Development ; Environmental Movement: Role of Water in the ; Fisheries, Fresh-Water ; International Cooperation ; Lake Management Issues ; Pollution by Invasive Species ; Pollution of Lakes and Streams ; Pollution Sources: Point and Nonpoint ; Ports and Harbors ; Recreation ; Tourism ; Transboundary Water Treaties ; Transportation .

Faye Anderson

and William Arthur Atkins

Bibliography

Ashworth, William. Great Lakes Journey: A New Look at America's Freshwater Coast. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2000.

MacKenzie, Susan Hill. Integrated Resource Management: The Ecosystem Approach in the Great Lakes Basin. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1996.

Internet Resources

Great Lakes Commission. <http://www.glc.org/> .

Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. <http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/> .

Great Lakes Fishery Commission. <http://www.glfc.org> .

Great Lakes Information Network. <http://www.great-lakes.net/> .

International Joint Commission. <http://www.ijc.org> .

The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book Government of Canada and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. <http://www.epa.gov/glnpo/atlas/intro.html> .

LAKE SUPERIOR IS APTLY NAMED

Lake Superior is the largest lake with respect to both surface area and volume of water. It is also the deepest and coldest of the five lakes. If filled with the smaller lakes, Lake Superior could contain each of the other four Great Lakes and three more lakes the size of Lake Erie. The northwestern section of Lake Superior contains the archipelago of Isle Royale National Park.

* See "Army Corps of Engineers, U.S." for a photograph of a vessel at the Soo Locks.

* See "Fisheries, Fresh-Water" for a photograph of a recreational fisher holding a Lake Michigan steelhead.

* See "Environmental Movement, Role of Water in the" for a photograph of the 1952 Cuyahoga River fire.

If there is anyone, please reply with the questions asap. (This is for my school project, I need a interview from someone dealing with this issue. I am in grade 9 and I go to a high school in Toronto. My project is due Tomorrow so please reply asap.)

Q. What is the name/title of your job?

Q. Can you briefly explain what your job is all about?

Q. What is the name of the lake that you are working on?

Q. What role are you playing in the issue of great lakes shoreline development?

Q. Where do you stand in this issue/what kind of responsibilities do you have?

Q. What are some of the difficulties or problems that you are facing while dealing with this issue?

Q. What specifically are you doing to help/hinder the resolution process?

Q. Do you think what you are doing is environmentally friendly?