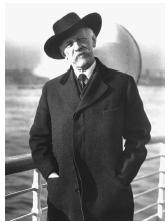

Nansen, Fridtjof

Norwegian Arctic Explorer and Oceanographer 1861–1930

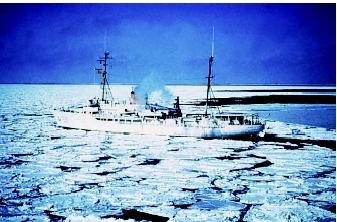

The science of oceanography was in its infancy in 1893 when Fridtjof Nansen, a 32-year-old Norwegian, purposely allowed his ship, the Fram, to be captured in an Arctic ice pack. Through this deliberate act, Nansen hoped to prove his theory that the Arctic current flowed from Siberia towards the North Pole and then southward to Greenland. The way to show this to be true, Nansen reasoned, was to create a specially built ship that would not be crushed by ice so that he could drift in the ship wherever the ice pack moved. If the Fram (meaning "Forward") was carried close enough, Nansen also hoped to become the first person to reach the North Pole.

Greenland Ice Cap

Nansen thought in original ways. While a university student in Christiana (now Oslo, Norway), he took a voyage in 1882 to Arctic regions aboard a seal-hunting ship. Nansen kept records of winds, ice movements, and animal life. On this voyage, he became intrigued with the idea of ocean currents while observing the eastern coast of Greenland. He decided to attempt

With a team of five, Nansen accomplished this trek in 1888. One of the more unusual aspects of the expedition was the direction he chose to travel; the team went from east to west across Greenland instead of the more usual west-to-east direction. Nansen decided that because it was impossible for a ship to wait off the inhospitable east coast once his team had disembarked, he and his men would be forced to move toward the inhabited west coast, where their ship could safely meet them.

It was a plan that worked. Nansen had become the first person to cross Greenland's ice cap. His observations on this trip demonstrated that continental glaciers are thick and heavy enough to depress the Earth's crust beneath their weight. His work provided support for the theory of isostatic rebound—the idea that when the Earth's crust sinks under a heavy weight, it will slowly return to its original position when that weight is removed.

The Fram Expedition

By the time he returned home to Norway, Nansen was famous. Yet people thought him foolish in planning his next voyage—one in which he would purposely let his ship be caught up in the Arctic ice. They reasoned that the Fram would be crushed; or, if by some miracle the vessel escaped destruction, then his crew would become insane by virtue of being trapped on a ship for several years without any contact with the outside world.

But attention to detail was Nansen's strength. He found a shipbuilder who designed the Fram as an iron-clad, three-hulled ship able to be thrust up and not crushed by the pressure of ice. The propeller and rudder would be built into the ship to protect them.

Nansen knew his team would be constantly busy making scientific observations. But for the infrequent off-hours, he put a library, musical instruments, and games onboard to entertain the crew. To captain the ship, Nansen chose Otto Sverdrup, one of the men who had crossed Greenland with him.

Successful Journey.

Nansen's meticulous planning paid off. His trip was successful, and had a most unusual finale. Because the Fram did not drift as close to the North Pole as he had hoped, Nansen decided to make an overland dash for it. With one companion, dogs, sleds, and kayaks, he left the Fram under the capable care of Sverdrup and, in March 1895, headed for the Pole. Conditions forced the two men to turn back, but they had gotten closer than anyone as of that date. After a demanding journey of 483 kilometers (300 miles), they made it to a safe wintering place, an island in Franz Josef Land.

After breaking camp in the spring, Nansen and his companion headed south and had a wonderful piece of luck. On the ice and in the middle of nowhere, they met the leader of a British scientific expedition who sent them home to Norway in one of his ships. They arrived in their country on August 13, 1896, the same day the Fram finally became free of pack ice and also headed home. The ship had done exactly what Nansen predicted—drifted with the Arctic current. His work provided enormous knowledge about the currents, climate, and marine life of the Arctic Ocean.

Later in Life

From 1896 to 1917, Nansen served as a professor at the University of Christiania, where he performed research in oceanography. He published a sixvolume report of the Fram expedition that remains a major reference on the Arctic Ocean. He also designed several instruments still in common use, including the Nansen bottle, a device used to collect pure samples of sea water at given depths. Several scientific voyages to the North Atlantic added to his knowledge.

As a statesman, Nansen worked for the peaceful separation of Norway from Sweden. His efforts were rewarded by an appointment as Norway's first minister to Great Britain from 1906 to 1908.

Toward the end of World War I, Nansen became internationally known for his service to famine-stricken Russia as well as for his work in returning prisoners of war to their homes. His contributions won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

SEE ALSO Glaciers and Ice Sheets ; Ice Ages ; Ice at Sea ; Ocean Currents ; Oceans, Polar .

Barbara Johnston Adams

Bibliography

Huntford, Roland. Nansen: The Explorer as Hero. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1997.

Nansen, Fridtjof. Farthest North. New York: Modern Library, 1999.