Law of the Sea

The oceans have long been viewed by societies as a wide-open free space—a vast frontier associated with adventure and mystery. In the seventeenth century, nations formalized this viewpoint into the Freedom of the Seas doctrine. This doctrine limited any nation's rights to the ocean to a narrow belt, traditionally 4.8 kilometers (3 miles), surrounding its coastline and declared the rest of the seas to be free to all nations and belonging to no one. This doctrine formalized views that the seas were such a vast resource that all nations could use them as they wished.

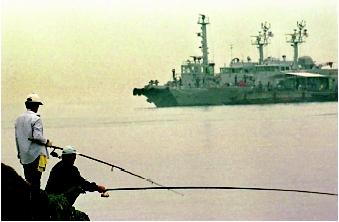

Dramatic growth in use of the oceans directly challenged this doctrine by the twentieth century. The ocean's resources were increasingly used for economic uses, and nations desired to extend their claims over offshore resources. Fishing fleets, transport ships, oil drilling, and military navies all relied on the seas for their success. Concern grew over the impact of these uses and many conflicts emerged between nations over rights to the resources.

Growing Conflict over Ocean Uses

In the United States, president Harry Truman directly challenged the Freedom of the Seas doctrine in 1945 by unilaterally extending the nation's jurisdiction to its coastal waters. He extended the United States rights to a wider band to include all of the resources on the continental shelf , including oil, gas, and minerals. Partly, he was acting in response to pressures from the U.S. oil industry that eyed profitable reserves offshore.

Many nations followed Truman's lead and extended their sovereign national rights to the seas as well. In 1950, Ecuador claimed rights to a 322kilometer (200-mile) zone. Indonesia and the Philippines asserted rights over all waters separating their islands. The vast resources derived from the oceans countered the viewpoint that it was a free space. As new technologies increased human abilities to exploit those resources, conflicting claims multiplied and nations further desired to expand their territorial rights. The human relationship with the seas had dramatically changed.

United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea.

In 1967, Arvid Pardo, Malta's ambassador to the United Nations, called on the nations of the world to recognize their potential devastation of the oceans and the importance of the oceans to world peace. He pleaded for "an effective international regime over the seabed and the ocean floor beyond a clearly defined national jurisdiction." This began a 15-year process to create a management mechanism for the world's seas.

The United Nations Seabed Committee was formed and, after much preparation, met in 1973 in New York to draft an international treaty for the oceans. Nine years of negotiations between more than 160 nations over national rights and obligations ensued. In 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted at the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea. The Convention needed 60 states to sign on to ratify it, and it came into force in 1994.

Law of the Sea

The Law of the Sea (LOS) is a comprehensive treaty covering territorial sea limits, navigational rights, the legal status of the ocean's resources, economic jurisdictions, protection of the marine environment, marine research, and other facets of ocean management. It attempted to address the existing conflicts over the oceans. After its adoption, some called it "possibly the most significant legal instrument of this (the twentieth) century."

The treaty established legal principles governing ocean space, its uses and resources. The Law of the Sea treaty also set up a binding procedure for settling disputes between nations and established the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. Nations could now take other nations to court over perceived violations of international convention. The treaty also recognized the right to conduct marine scientific research. It addresses the main sources of ocean pollution: land and coastal activities, continental shelf drilling, seabed mining, ocean dumping, and vessel-source pollution.

The Law of the Sea also established the International Seabed Authority, which regulates activities in the deep seabed beyond national jurisdictions. One of the most contentious aspects of the Law of the Sea was the language dealing with the mining of minerals in the deep ocean floor, the part of the international seabed area beyond the national jurisdictions (Part XI). In 1998, an agreement was passed, formally known as the Agreement Related to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention. This Agreement in jointly implemented with the LOS.

The Ocean's Future.

The joining of the world's countries to protect the oceans through the Law of the Sea Convention signals society's growing recognition of the importance of the oceans to life on Earth. The Law of the Sea is a good example of intergovernmental cooperation to protect an important resource from global pressures. The ocean's future depends on the abilities of nations to implement effective governance.

SEE ALSO Conflict and Water ; Legislation, Federal Water ; Mineral Resources from the Ocean ; Petroleum from the Ocean ; Sustainable Development .

Faye Anderson

Bibliography

Wang, James C. F. 1991. Ocean Politics and Law: An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1991.

Internet Resources

Atlas of the Oceans. United Nations. <http://www.oceansatlas.org/index.jsp> .

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. <http://www.itlos.org/> .

NOAA Ocean Page. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. <http://www.noaa.gov/ocean.html> .

Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. United Nations. <http://www.un.org/Depts/los/index.htm> .

EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE

An Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is one of the tools defined by the Convention on the Law of the Sea. In the eighteenth century, the cannon-shot rule governed a nation's claims to territorial seas, based on the distance that projectiles could be fired from a cannon onshore—at that time, about 4.8 kilometers (3 miles). The Law of the Sea built on this idea and expanded the zone to 322 kilometers (200 miles).

Today, nations have the right to develop, manage, and conserve all resources in waters, on the ocean floor, and in the subsoil in the area extending 322 kilometers (200 miles) from its shore. These EEZs bring many benefits to countries, because lucrative fishing, oil, and other reserves often lie within these zones.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: