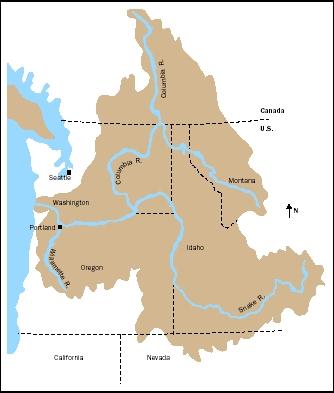

Columbia River Basin

The Columbia River is one of the most dominant environmental features of the Pacific Northwest. Beginning high in the mountains of southeastern British Columbia, the Columbia River flows 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles) through alpine and subalpine environments, montane forests, lava fields, semiarid grasslands, and low-elevation rainforests before entering the Pacific Ocean.

Draining more than 671,000 square kilometers (259,100 square miles), the Columbia River Basin is the fourth largest river basin in the United States. It encompasses seven states (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Nevada, and Utah) and one Canadian province (British Columbia), more than a dozen Indian reservations, and numerous local jurisdictions. This complex physical and jurisdictional landscape makes managing the Great River of the West an exceptional challenge.

Native and Non-Native Settlement

Archaeologists have found evidence of human occupation of the Columbia River Basin dating back more than 10,000 years, though many of the basin's Native peoples argue that they have always been in the region. The Columbia River was and still is a central feature in the life of Native peoples, providing food, water, and transportation. Salmon was a keystone resource, providing a significant percentage of their protein; it was also an important trade item. Despite thousands of years of heavy use, under Native peoples' stewardship the Columbia River remained a diverse, highly productive ecosystem well into the nineteenth century.

Non-Native peoples began moving into the basin in notable numbers during the 1840s and 1850s, pushing Native peoples onto reservations and imposing a radically different management regime on the river. Early non-Native use of the river paralleled that of the Indians'—fishing for salmon, using the river as a transportation conduit, locating settlements on the flat, fertile floodplains. But as technology evolved and the basin's population expanded in the latter half of the nineteenth century, demands on the river greatly increased. Irrigation ditches, hydroelectric dams, commercial fisheries, the dredging of navigation channels, and the input of pollutants had all effected major changes in the river's physical and biological characteristics by the early twentieth century.

While many of the Columbia's tributaries were dammed and ditched in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was not until the 1930s that the mainstem of the Columbia was developed. Responding to the Great Depression, the U.S. government built Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams, the latter of which was the largest dam in the world at the time and is still the country's largest single power producer. Today there are more than 400 dams in the basin, including 14 on the mainstem—projects that generate an average of 12,000 megawatts a year, accounting for about 40 percent of the United States' hydroelectric power and for up to 75 percent in the Pacific Northwest. The total hydropower production of the Columbia system roughly equals 20 nuclear power plants running full-time.

Impacts of Dams

The dams on the Columbia River and its major tributaries form the backbone of the Pacific Northwest's economy, providing power to homes and industry, controlling floodwaters, irrigating hundreds of thousands of hectares of farmland, and forming an extensive navigation system. However, these benefits have come at an exceptionally high environmental cost.

Annual runs of Columbia River salmon have declined from an estimated 8 to 16 million to an average of fewer than 1 million, and a dozen stocks have been listed as either threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. In addition to blocking access to spawning grounds, dams alter the seasonal flow of the river, prevent juvenile salmon from migrating downstream to the ocean, increase the abundance of fish predators, and change water quality by raising the temperature and increasing the amount of nitrogen in the water.

Though dams are a major factor in the decline of salmon, they are not the only one. Overfishing, logging, irrigation withdrawals, urban pollution, channelization , road construction, the introduction of nonnative fish, and other activities have also contributed to the decline of salmon and other native fish populations.

Institutional Complexities

While river management in the Columbia River Basin historically focused on the creation of economic benefits (e.g., hydroelectric power and flood control), the focus in recent years has shifted to ecosystem management and restoration. Salmon have been at the center of this important shift in management philosophy, but a variety of obstacles have stood in the way of effective restoration.

Some argue that one of the most significant obstacles to successful integrated ecosystem management is institutional fragmentation. The Columbia River Basin is under the jurisdiction of two countries, several states, more than a dozen tribes, and numerous local agencies. Even among federal river managers there is a substantial amount of institutional fragmentation. The Bonneville Power Administration, for instance, markets power produced at dams built and managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation, while the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission oversees nonfederal dams (those built by private companies and public utility districts).

The National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manage the river's fish and oversee the implementation of the Endangered Species Act; the former manages marine fish and wildlife, the latter manages fresh-water fish and wildlife. The Environmental Protection Agency is charged with implementing the Clean Water Act, ensuring that federal agencies and other entities meet water quality standards in the Columbia and its tributaries. The Bureau of Indian Affairs ensures that tribal rights are recognized, especially the 1855 treaty right to take fish at usual and accustomed fishing places. The U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management manage a large portion of the basin's land, overseeing logging, grazing, recreation, and other land-based activities, many of which have direct impacts on aquatic habitats.

Finally, the Northwest Power Planning Council, a unique regional agency that is neither federal nor state-based but rather somewhere in between, helps plan power production, energy conservation, and fish and wildlife restoration activities throughout the basin. Add in the dozens of state agencies, tribal agencies, and local agencies, and one gets a picture of the complexity of the institutional landscape and the challenges river managers face in trying to restore the region's fish and wildlife populations to healthy levels.

It took 150 years for the health of the Columbia River to decline to the condition it is in today. Hundreds of dams impound the river and its tributaries, more than half a dozen fish species are at risk of extinction, and pollutants ranging from human sewage to radioactive wastes flow through the river and into the ocean. Private, local, state, and federal management activities, while undoubtedly providing many benefits, are directly responsible for this state of affairs. The recent shift to restoration and ecosystem management is largely in response to this decline in ecosystem health, but these new management approaches are still in their infancies and face many difficult challenges in the years to come. Only time will tell if they will be as socially and politically successful as more traditional management approaches.

SEE ALSO Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. ; Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. ; Clean Water Act ; Dams ; Endangered Species Act ; Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. ; Fisheries, Marine ; Hydroelectric Power ; Lewis, Meriwether and William Clark ; Planning and Management, History of Water Resources ; Planning and Management, Water Resources ; River Basin Planning ; Salmon Decline and Recovery ; Transportation .

Cain Allen

Bibliography

Blumm, Michael C., and Brett M. Swift, eds. A Survey of Columbia River Basin Water Law Institutions and Policies: Report to the Western Water Policy Review Advisory Commission. Portland, OR: Northwestern School of Law, 1997. Available online at <http://www.waterinthewest.org/reading/readingfiles/fedreportfiles/col2.pdf> .

Cone, Joseph, and Sandy Ridlington, eds. The Northwest Salmon Crisis: A Documentary History. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1996.

Dietrich, William. Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995.

Federal Caucus. Conservation of Columbia Basin Fish: Building a Conceptual Recovery Plan. Spokane, WA: Federal Caucus, December 1999. Available online at <http://www.salmonrecovery.gov> .

Independent Scientific Group. Return to the River: Restoration of Salmonid Fishes in the Columbia River Ecosystem. Portland, OR: Northwest Power Planning Council, 2000. Available online at <http://www.nwcouncil.org/library/return/2000–12.htm> .

Lang, William L., and Robert C. Carriker, eds. Great River of the West: Essays on the Columbia River. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

White, Richard. The Organic Machine: Remaking of the Columbia River. New York: Hill & Wang, 1995.

Internet Resources

Center for Columbia River History. <http://www.ccrh.org> .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: