Careers in Environmental Education

Educating others in environmental principles and theories is a rewarding activity, and one that some individuals pursue as a full-time profession. Environmental education has evolved over the last century from a oncesmall field of environmental interpretation to a growing discipline with new opportunities steadily arising.

Moreover, environmental issues have become increasingly important worldwide, and crucial decisions must be made with respect to balancing the use of resources, the needs of other organisms, and the economy. Environmental educators can provide an appreciation for the scientific method and the data behind these complex issues, leading to a better-informed populace. For example, teaching students and the public how data are collected and interpreted will give them a realistic view of information that influences the decision-making process. An informed public is likely to ask "Where and how were the data collected?" and "What are the assumptions and the alternative hypotheses?"

From Interpretation to Education

Environmental interpretation was a forerunner of environmental education, and was first undertaken on a broad scale by the National Park Service during the mid-twentieth century. Interpretation is defined as an educational activity that aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of natural objects, by first-hand experience, and by illustrative media, rather than simply relating scientific principles in a formal classroom setting.

The uniformed park ranger presenting an evening campfire program or an interpretive nature walk was an early form of environmental education. These types of programs were designed for a short-term, passive, noncaptive audience. Most visitors to natural areas simply desired to learn a little about the natural world while in an outdoor or on-site setting.

By the 1970s, traditional educators began to see a need to bring these educational activities into the classroom. The public's knowledge of the natural world was increasing, as well as awareness of the need for environmental protection and stewardship. Most states began to require an environmental education component in their established educational goals and benchmarks for K–12 students. Hence, environmental education came into existence.

Types of Work

Most K–12 science teachers consider themselves multidisciplinary instructors, rather than environmental educators. A need therefore exists for curricula to fulfill state requirements, and workshops that enhance teacher training in environmental sciences as well as in presentation methods.

Environmental education today combines both the principles of interpretation and formal science education. The overall goal is to teach environmental science in ways that are enlightening and enjoyable. This usually requires a combination of classroom work supplemented with outdoor field studies. The integration of traditional science with interpretive techniques is the greatest challenge environmental educators encounter. Many K–12 educators supplement their instruction by bringing in guest speakers who are professionals in environmental disciplines.

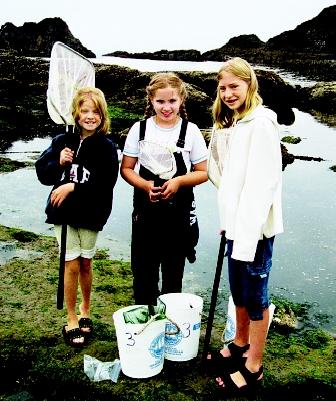

Most quality environmental education programs use an inquiry approach to learning. Students learn the basic principles and theories of environmental science and then apply them to the real world through the completion of research projects, field investigations, and hands-on activities. Work is performed outdoors, as well as in the classroom and at visitor centers. Some agencies and private companies have developed programs that offer unique opportunities, including floating classrooms on a research vessel where students can study oceanography, marine biology, and water science. Internships at local, state, and federal agencies may provide additional opportunities.

Employment Opportunities

The employment outlook for environmental educators is good as a result of increasing public awareness and demand for information. The need for up-to-date curricula that educators can use in their classrooms is of prime concern, and many companies and universities hire staff primarily for that purpose.

Field trips are a necessary facet of environmental education. Most aquariums, natural history museums, zoos, and recreation departments have staff and curricula which teachers can access. Many private groups provide field instruction on land as well as on lakes, rivers, and oceans.

Agencies and private companies with an environmental aspect to their activities often utilize public relations staff that can easily relate to the public. Environmental educators are uniquely qualified for such positions. Federal agencies such as the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have staff and programs that directly serve K–12 education. There are also opportunities for adult environmental education curricula and classes, but these programs are in early stages of development, showing a need for more curricula development in the future.

Academic Preparation

Environmental education is one of only a few professions that consider the Earth as an entire system, and not just the sum of its parts. To prepare for a career in environmental education, students must become well versed in many different disciplines rather than specializing in just one field. Students

Ecology, chemistry, geology, marine biology, aquatic science, and oceanography are all important if students wish to work in water science education careers. Mathematics is high on the list, as most studies relating to water science involve the use of mathematical formulas and statistics. Computer science and graphic design skills are prerequisites for those wishing to develop environmental education curricula that will satisfy audiences who increasingly prefer visual information.

SEE ALSO Ecology, Fresh-Water ; Ecology, Marine ; Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. ; Geological Survey, U.S. ; National Park Service ; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ; Recreation ; Tourism .

Ron Crouse

Bibliography

Golley, Frank B. A Primer for Environmental Literacy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

Hale, Monica, ed. Ecology in Education. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Ham, Sam H. Environmental Interpretation, A Practical Guide. Golden, CO: North American Press, 1992.

Tilden, Freeman. Interpreting Our Heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Internet Resources

National Environmental Education and Training Foundation. <http://www.neetf.org> .

Environmental Education. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. <http://www.epa.gov/enviroed> .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: